Taiwan's New Tech Dreams

BusinessWeek

By: Bruce Einhorn

November 12, 2009

At the depth of the global economic crisis, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSM) was in trouble. With factories operating at just a fraction of capacity, Morris Chang—TSMC's silver-haired founder—laid off hundreds of staffers, ordered the remaining workers to take unpaid leave, and took other cost-cutting steps such as dimming the lights in hallways. "It was terrible," Chang says in his office on the eighth floor of "Fab 12," a vast facility that serves as TSMC's headquarters.

These days, things look far better. TSMC's plants are humming again, and its Taipei-listed shares are up 41% this year. But Chang is chastened. The era of easy double-digit growth for chipmakers "isn't there anymore," he says, taking a puff on his ever-present pipe. "We need to find new areas." TSMC is stuck in a maturing industry, and its primary business of making chips for other companies is likely to grow just 8% annually in coming years. So Chang wants to boost TSMC's presence in solar power and light-emitting diodes (LEDs). The two have technological overlap with chip production, but they offer far better margins and more potential. "They are going to be fast-growth industries," Chang says.

Executives across Taiwan's tech industry are making similar strategic shifts. Shi-Wei Sun, chief at chipmaker United Microelectronics (UMC), in August launched a division focusing on solar and LEDs. Peter Chou, CEO of smartphone maker HTC, is reducing his company's reliance on Microsoft Windows-based handsets, adding more phones using Google's Android operating system. And Au Optronics (AUO) is plotting a move beyond its traditional LCD displays, which require investments of billions of dollars every few years for companies to stay ahead of rivals. "Coming out of the recession, AUO is a completely different company," says C.T. Liu, chief of AUO's consumer display business. First up, he says, will be e-readers and electronic paper, newfangled displays that can be rolled or folded. Both technologies will let AUO capitalize on its display-making expertise.

Why the urgent shifts? While Taiwan plays a vital role in the global tech industry, it is strongest in low-margin businesses such as PCs and components. That has created a dead end for many manufacturers, which face constant pressure from Hewlett-Packard (HPQ), Dell (DELL), Sony (SNE), and other big customers to cut prices. "The business model is kind of hitting the wall," says Bill Wiseman, a partner with McKinsey in Taipei. So companies are preparing for the post-PC era by diversifying into other, more mobile devices and building up their own brands.

True, things aren't exactly dire for the island's tech titans. The Taiwanese benchmark index of electronics stocks is up 76% and, thanks largely to strong demand from China, orders keep coming for more chips, PCs, and other devices. Taipei has become one of Asia's most livable cities: With so much of its heavy industry now on the mainland, the air is much cleaner than in years past. And with relations between Beijing and Taipei on the mend, increasing travel and trade between the two sides will speed integration and further lift the Taiwanese economy. Taipei's Songshan Airport, for decades a sleepy terminal for short hops across the island, now buzzes as the hub of direct flights to mainland cities. Chinese authorities "are much friendlier" toward Taiwanese, says HTC Chairman Cher Wang, who recently jumped on a plane in Chengdu at noon and was back in Taipei by 3 p.m. "They feel that we're brothers who used to have a dispute but now are settling," she says.

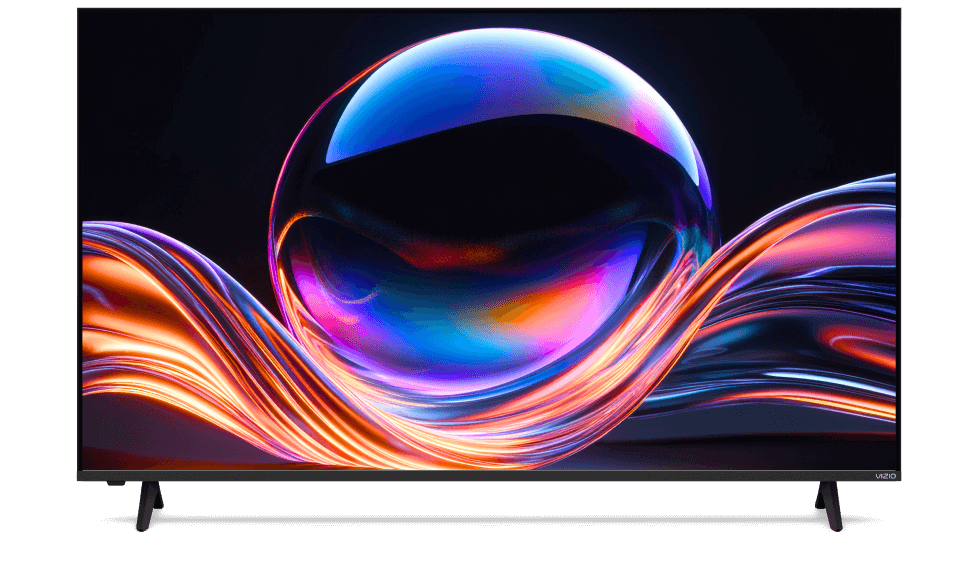

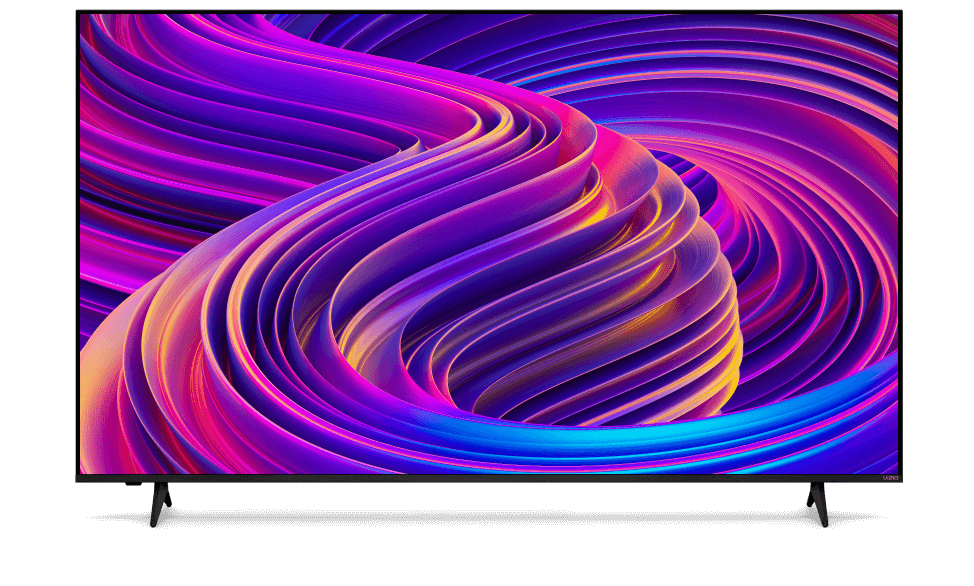

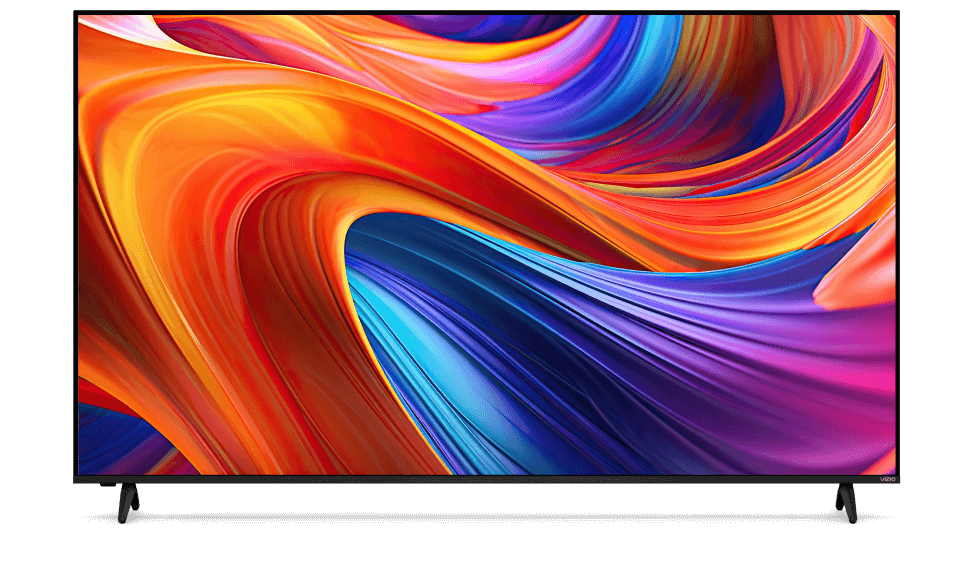

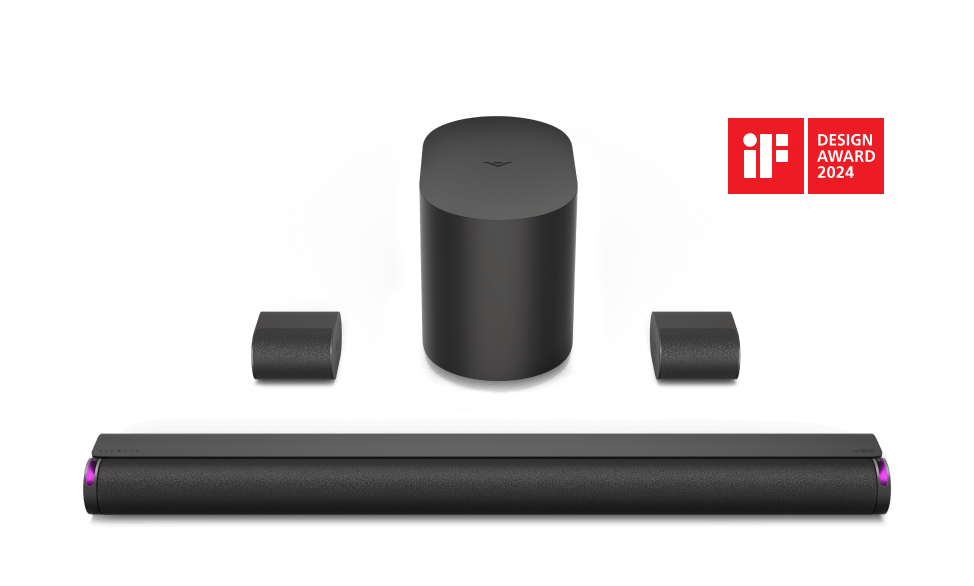

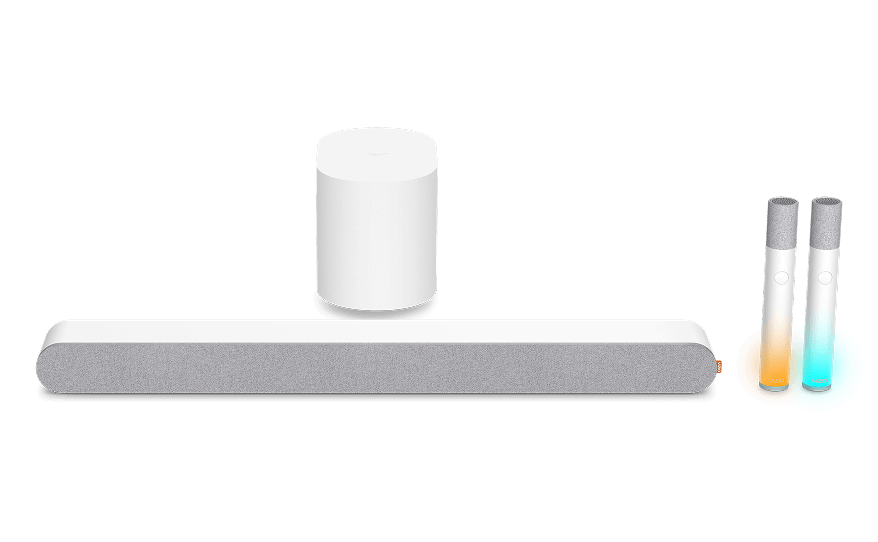

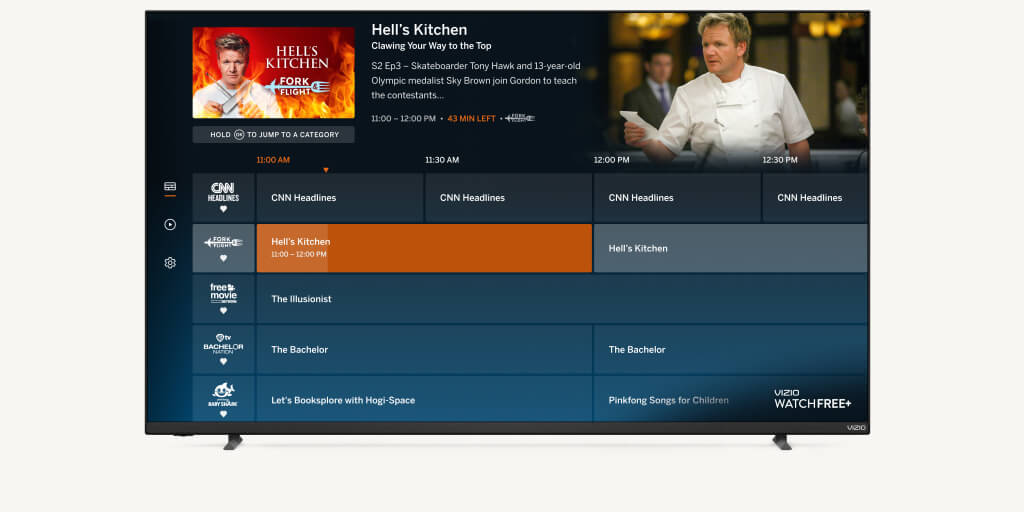

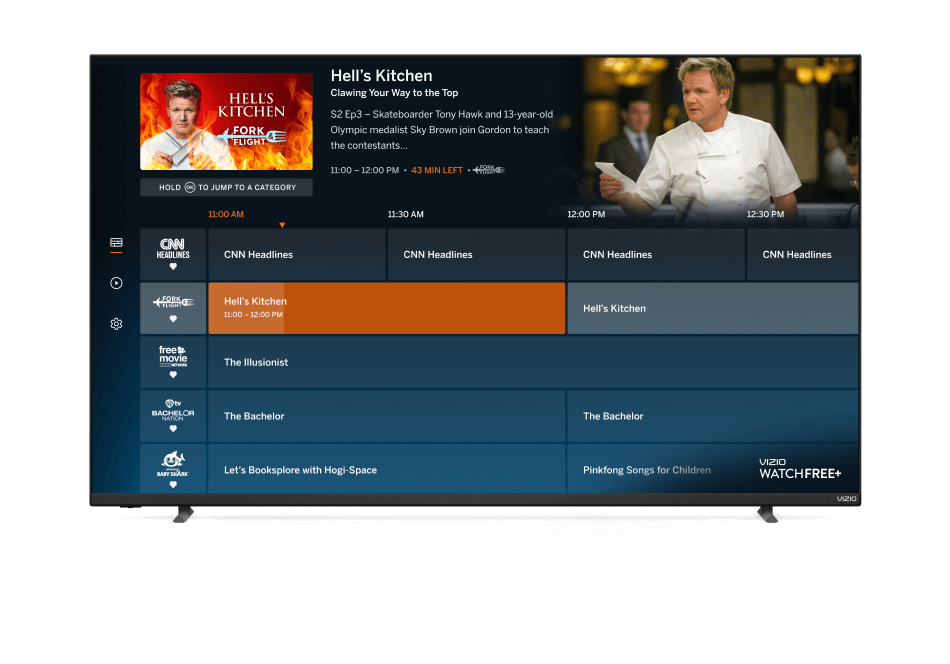

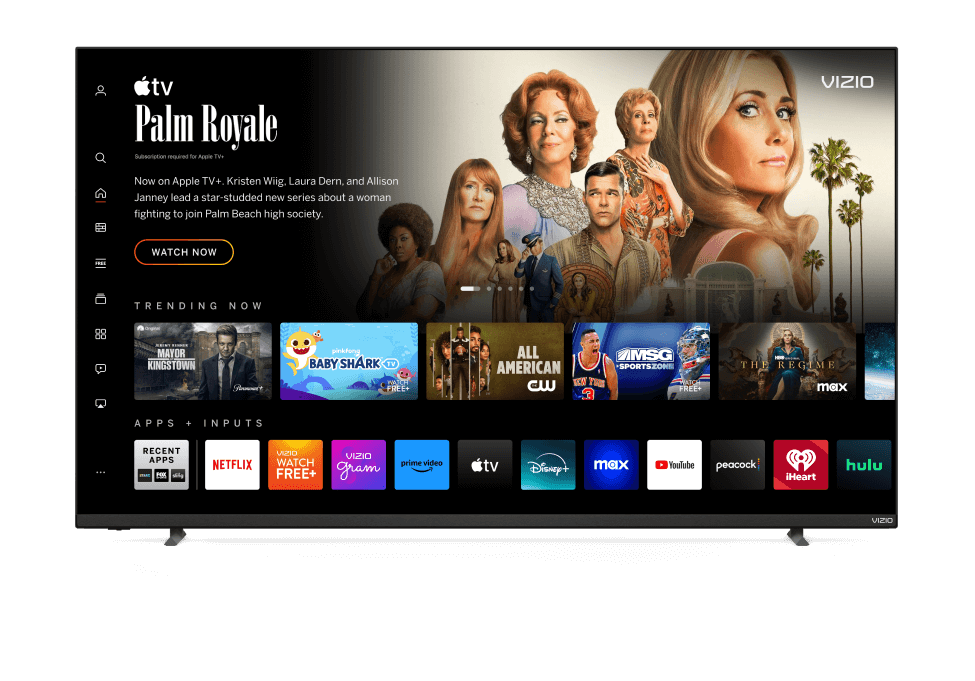

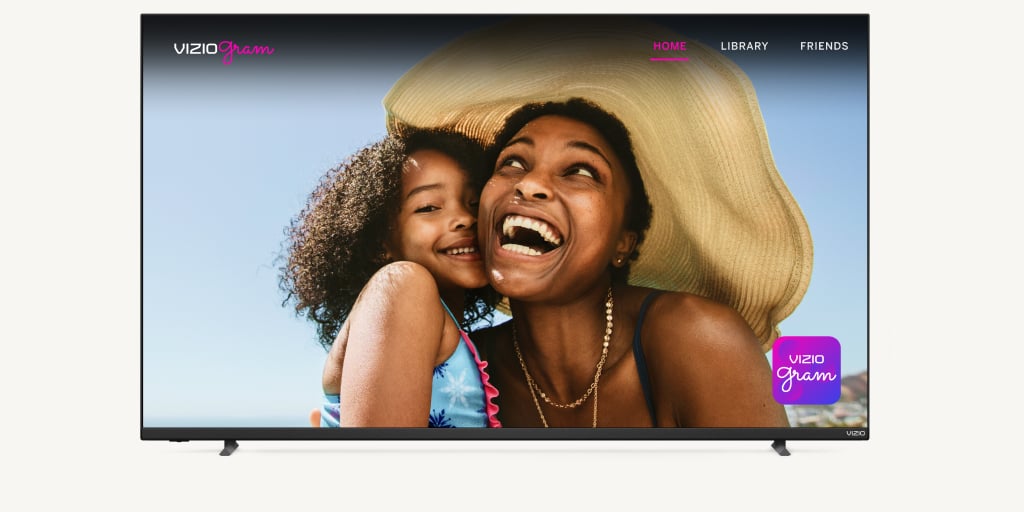

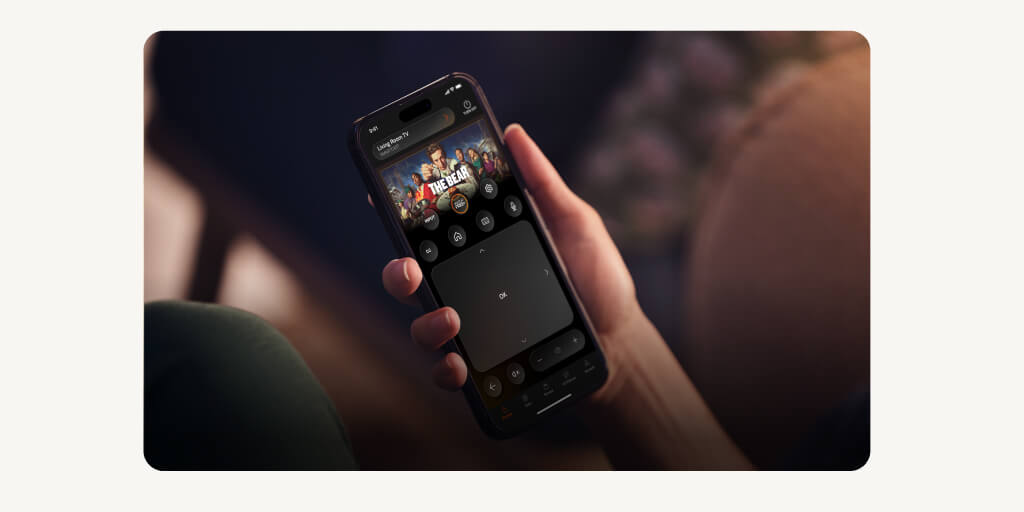

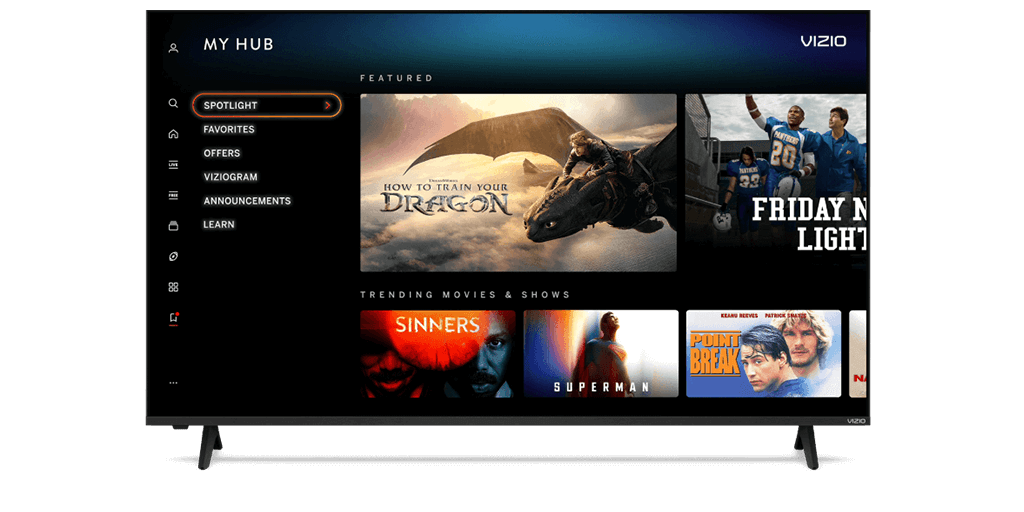

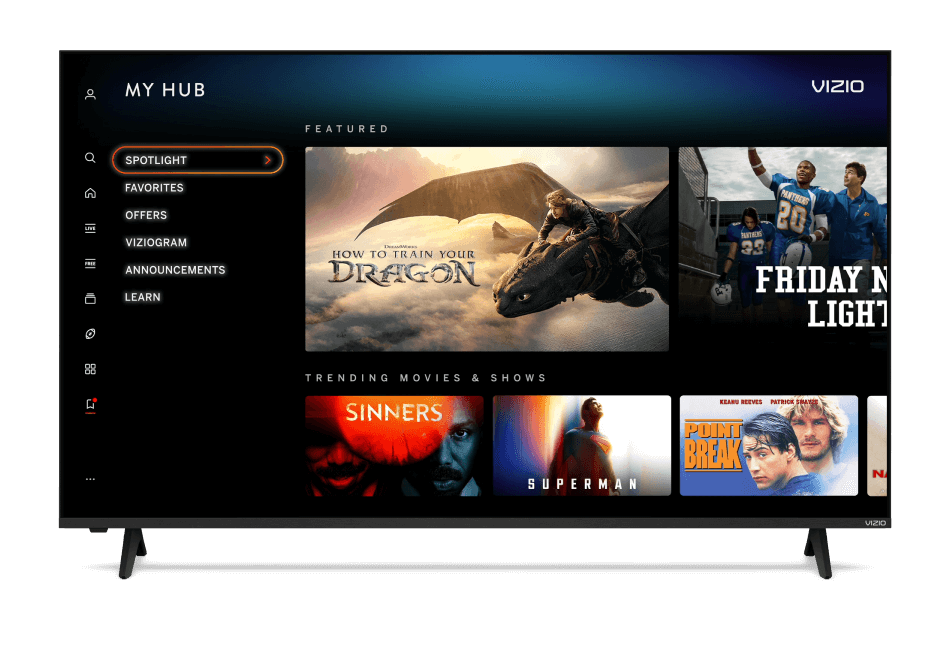

Still, as last year proved, things can turn south quickly, something many Taiwanese tech companies fully understand. So Acer, which last summer passed Dell to become the world's No. 2 PC company (behind Hewlett-Packard (HPQ), is moving into products such as smartphones and other mobile devices. Vizio, produced by Amtran Technology—a 15-year-old company that got its start making PC monitors—is now a top-selling brand of flat-screen TVs in the U.S. And notebook maker Quanta Computer is mulling production of devices such as cameras, gaming machines, and medical sensors. "Quanta will become a brand new company from now on," vows Chairman Barry Lam.

Taiwanese companies seeking to diversify might want to follow Simon Lin's lead. He is CEO of Wistron, the manufacturing arm of Acer that was spun off in 2002 when Acer decided there was no glory in being a contract manufacturer. Wistron still shares with Acer a drab office tower in the low-rent Taipei suburb of Hsichih. The neighborhood is no match for Hsinchu, the giant tech park where TSMC has its digs, but it fits with Wistron's low-key, low-cost image. The company, which had revenue of $13.5 billion last year, has already expanded far beyond PCs, making TVs and BlackBerry smartphones.

More ambitious diversification is coming soon. Lin, fresh from a Taipei meeting with Microsoft (MSFT) CEO Steve Ballmer, says the devices Wistron makes in the years ahead will have to connect to the Internet but won't necessarily be computers. Lin also wants Wistron to develop businesses such as equipment repair and recycling, which is sure to pick up as more governments mandate clean disposal of old tech gear. To that end, Wistron in October invested $8 million in a company that recycles computer motherboards. Within a few years, Lin predicts, Wistron could have a $1 billion business in tech recycling. "No one has a crystal ball to say how long [the PC business] will last," he says. "But we are not sitting here just waiting for the sunset of the PC industry."

While PCs may rebound next year as the economy picks up and companies upgrade to Windows 7, they will surely be a smaller part of the tech mix as the market shifts. And the island's electronics makers will thrive in that post-PC era, says Jen-Hsun Huang, CEO of chipmaker Nvidia, who grew up in Taiwan before moving to the U.S. "If every cell phone in the world becomes a mobile computer, if every TV becomes a connected TV," he says, "holy cow!"